Being seen and feeling cared for — Migrants community emergency plan during the pandemic

The infection rate and death toll of COVID-19 pandemic had far exceeded expectations, dealing a heavy blow to the physical, mental and economic health of citizens. The situations of marginalised labour, for example migrant workers, had been especially dire.

“During the first days of the outbreak, many migrant workers were not provided face masks and hand sanitisers, and had to use their meager salary to buy anti-epidemic products at inflated prices. Their hometowns were also impacted, and many workers had to make extra remittances to support their out-of-job family members,” said Eni Lestari, the chairperson of International Migrants’ Alliance. She pointed out that even though many migrant workers were cash-strapped, they were ineligible for the consumption vouchers issued by the Hong Kong SAR Government, and were locked out of necessary aid.

“During the first days of the outbreak, many migrant workers were not provided face masks and hand sanitisers, and had to use their meager salary to buy anti-epidemic products at inflated prices. Their hometowns were also impacted, and many workers had to make extra remittances to support their out-of-job family members,” said Eni Lestari, the chairperson of International Migrants’ Alliance. She pointed out that even though many migrant workers were cash-strapped, they were ineligible for the consumption vouchers issued by the Hong Kong SAR Government, and were locked out of necessary aid.

In addition to being financially crippled, it was more difficult for migrant workers to access pandemic information compared to Hong Kong citizens. Due to language barriers, they couldn't get daily updates on time, such as the new information about different anti-pandemic policies, social distancing policies, epidemic prevention measures, what should be done if infected, and so on. Dolores Balladares, Chairperson of United Filipinos in Hong Kong, said, “When the outbreak started, the Government didn’t prepare pamphlets specifically written in the migrant workers’ mother languages. Even if they have them now, the pamphlets were only telling us not to congregate, and they were only distributed in scarce locations where migrant workers might gather. Social distancing measures and police dispersals have scattered workers and confined them to their immediate social circles, making it challenging to disseminate information en masse, thus increasing our risks of infection manyfold.”

Eni added that many employers forbade migrant workers to go out during days off, or demanded them to report their whereabouts with video chats. Workers were also required to clean the households more frequently than before, which added to their stress levels.

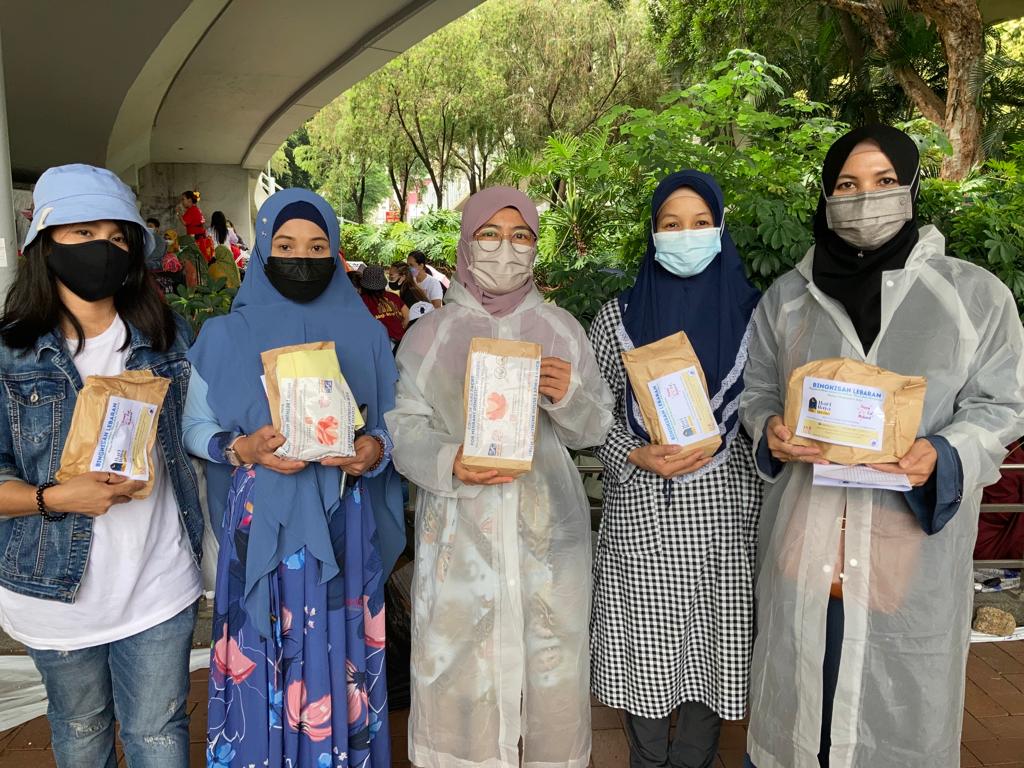

Communities were largely left to their own devices under Hong Kong’s fifth wave of pandemic. Migrant workers were just as frustrated, said Sringatin, Chairperson of the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union. “Without government support, migrant workers had to take their own initiatives to voluntarily outreach to others face-to-face on their day offs, and spread anti-epidemic information on their communities’ social media. Luckily, we received HER Fund’s grant, which covered our outreach volunteers’ transport fares, pamphlet printing, and the purchase of canned food, vitamin C and anti-epidemic products. It was such a warm gesture.”

Fifi, a member of the migrants solidarity committee of autonomous 8a, added, “under the pandemic, on one hand, we didn’t have the manpower to appeal to larger Grantmakers. On the other, many funders prioritised the anti-epidemic needs of local permanent residents. They (HER Fund) not only provided monetary support, but also allowed flexibility. For example, while executing our project, we realised the change in the community’s needs as the pandemic progressed. Therefore, we opted to buy nutritious canned food for migrant workers in need in addition to simply providing food subsidies to frontline volunteers.”

Sringatin thanked the efforts of volunteers and HER Fund’s timely assistance. “There were migrant workers who told me they were grateful for receiving food in time, which gave them sufficient nutrients to strengthen their immune systems and speed up their recovery.”

While emergency financial support played a part in transforming migrant workers’ helplessness into gratitude, it was the fact that they were being seen and cared for, some of the best comforts marginalised communities yearn for, that moved them the most.

Interviewed and written by: Lam Chi Chung

Translated by: Donald Cheung (Volunteer)